How Did the Emperors During the Tang to Qing Dynasties Influence Chinese Art History

The art of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) began to explore new possibilities in materials and styles with mural painting and ceramics, in detail, coming to the fore. New techniques, a wider range of colours and an increase in connoisseurship and literature on fine art are all typical of the menstruum. Non only produced by local artists, many fine works were created past foreigners from across Eastern asia and the increasing contact between China and the wider world led to new ideas and motifs being adopted and adjusted. The Tang dynasty was one of the golden eras of Chinese history and the brash confidence and wealth of the 24-hour interval are reflected in the vivid and innovative art information technology produced.

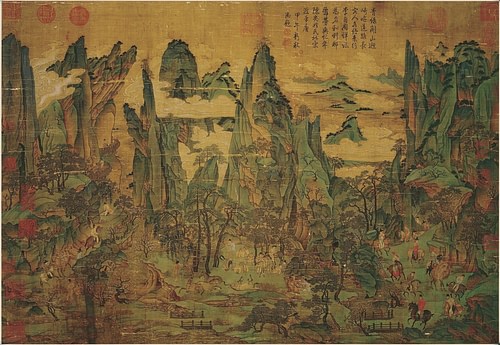

The Emperor Ming Huang Travelling in Shu

The Purpose of Art

The period of the Tang dynasty saw several pregnant developments in art from ceramics to brushwork and one of these, perhaps the most important, was an increase in the very appreciation of information technology as a worthy human attempt. At that place was a defended official at court, the Majestic Commissioner for the Searching out of Writings and Paintings; schools to train artists such equally the famous Hanlin Academy; and the first history of art was written past Zhang Yanyuan in 847 CE, titled Record of Famous Paintings of Successive Dynasties. The book has this to say on the purpose of painting:

Painting perfects the process of culture and brings back up to man relationships. It penetrates the divine permutations of Nature and fathoms the mysterious and subtle. Its achievement is the equal of any of the Vi Arts and it moves in unison with the four seasons. It proceeds from Nature itself and not from homo bamboozlement.

(Dawson, 205-vi).

It is worth noting that many Tang artists were likewise scholars, especially of Confucian principles, and they were frequently men of literature. Fine art was, for them and their audience, a means to capture and nowadays the philosophical approach to life which they valued. For this reason the fine art they produced is usually minimal and without artifice, perhaps sometimes even a little ascetic to western eyes. Tang fine art was meant to express the artist'southward good character and not merely be an exposition of his practical creative skills. Nevertheless, as we shall run into, the arrival of new technical possibilities to use more than colours and more dynamism would be embraced past professional person Tang artists in many media, a tradition which has remained present in Chinese art ever since.

Many Tang artists were also scholars, specially of Confucian principles, & they were frequently men of literature.

Sculpture

While the tombs of emperors and important people sometimes had big figure statues gear up outside them most Tang sculpture was of Buddhist subjects. The Buddhist monasteries of China had gradually and relentlessly been gathering wealth largely thanks to their land buying and exemption from taxes and, by the time of the Tang dynasty, this wealth permitted a great production of religious art. The most popular subjects, as ever, were the Buddha and bodhisattvas and ranged from miniature figurines to life-size statues. Unlike in previous periods, figures became much less static, their suggested flowing movement fifty-fifty drawing criticism from some that serious religious figures, on occasion, at present looked more than like court dancers. An excellent instance of Tang sculpture on the grandest scale can exist seen in the rock-cutting sculptures at the Longmen Caves, Fengxian temple nigh Luoyang. Dating to 675 CE the 17.4 metre high figures correspond a Buddhist Heavenly King and demon guardians.

Buddhist Sculptures, Longmen Caves

Calligraphy

The art of calligraphy, and for the ancient Chinese it certainly was an art, aimed to demonstrate superior command and skill using brush and ink. Calligraphy, already well-established as one of the major art forms during the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE), would influence painting where critics looked for the artist'south forceful use of brush strokes and their variation to produce the illusion of depth. Another influence of calligraphy skills on painting was the importance given to composition. Finally, calligraphy remained so of import that information technology even appeared on paintings to describe and explicate what the viewer was seeing. Eventually, such notes became an integral office of the overall composition and a part of the painting itself. It is no coincidence that many of the great Tang painters were as well great poets.

Paintings

Chinese painting on walls and silk had two main objectives: to capture people and landscapes. By the Tang dynasty the latter had finally overtaken the former as the most popular subject. As with sculpture, many Tang paintings had Buddhist themes simply, unfortunately, many have been lost, destroyed during the persecution of Buddhists and monasteries during the reign of Wuzong of Tang (840-846 CE). One excellent source of Tang paintings (and many other eras besides) is the Dunhuang caves in northern China. The cavern wall paintings prove scenes from the life of Buddha with many portraits of bodhisattvas and landscape scenes. Other notable tombs include that of the Tang prince Li Zhongrun (682-701 CE) which has an unfinished wall painting revealing the techniques involved. First, an outline sketch was fabricated on the plaster which was then covered in a white paint and sealed using a mixture of lime and glue. Finally, the desired colours were added and the black outlines repeated.

The historian M. Tregear describes the progress made in Tang Buddhist paintings as follows:

After the still richness of the Sui compositions, the Tang paintings erupt into activity. The huge paradise scenes love of the Amitabha sect, which was now dominant, are complex compositions showing palace and temple compounds in which crowds of mortals and immortals are disporting in a pleasure garden, with singing, dancing, word and preaching, and magical happenings. These compositions consist of an isometric project of the buildings seen from above, in which the figures are shown at eye level and usually out of scale. The colour is brilliant and decorative rather than atmospheric. The total effect is, once again, an constructing of the real and the supernatural which sparks the scene into life. These large compositions, whether pure landscapes or religious subjects, are the commencement of a long tradition in Chinese painting.

(Tregear, 87).

Fu Sheng past Wang Wei

Non-religious paintings, like Buddhist works, have not survived in any bang-up quantity either. For example, no piece of work is available of the famous portrait painter Wu Daozi (680-740 CE) who also adorned many court- and religious buildings with his murals. Daozi was said to have painted with such passion and verve that he attracted crowds to lookout him wherever he painted. Fortunately, some Tang tombs take provided portrait paintings of their occupants, including courtroom women, besides as animals such as lions.

Portraits in Chinese art were traditionally rendered with great restraint, usually considering the subject field was a bang-up scholar or court official.

There are, too, surviving paintings past the near celebrated courtroom scene painter Yan Liben (c. 600-673 CE) who famously painted a huge curlicue depicting 13 emperors but, alas, none by the leading landscape creative person Wang Wei (aka Mojie, 699-759 CE). The latter creative person is credited with inventing the horizontal moving picture curlicue (vertical pictures existence the convention until and so) and with creating the pomo or "broken ink" technique where washes of ink are painted in layers to create the issue of a solid, textured surface. He also pioneered the utilise of a unmarried color throughout a painting. Fortunately, some of his major works do survive every bit later copies and they are testimony to his influence on Chinese art in general and his success at achieving his objective of capturing both altitude and emptiness.

Portraits in Chinese fine art were traditionally rendered with groovy restraint, ordinarily considering the subject was a great scholar or court official and and so should, by definition, accept a good moral character which should be portrayed with respect by the artists. In that location were, however, instances of more realistic portraits. I example is the ii paintings of generals commissioned by Emperor Daizong which he hung exterior his bedroom to deed as guardians, such was the fearsome aspect of their portraits. The paintings would convince people in later times that the subjects were, in fact, door gods.

An Audience with Taizong by Yan Liben

In landscapes, Tang artists became much more concerned with humanity's place in nature. Minor human being figures guide the viewer through a panoramic landscape of mountains and rivers in Tang paintings whereas subsequently periods would see more intimate and abstract scenes of nature. Painting the scene with several different viewpoints and multiple perspectives is some other common feature. One of the nigh famous of all Chinese landscape paintings is the 8th century CE painted silk panorama known as 'The Emperor Ming Huang Travelling in Shu'. It is a sprawling and detailed masterpiece of mountain scenery in the typical Tang style using but blues and greens. The original is lost but a later on re-create can be seen at the Palace Museum of Taipei.

Ceramics & Minor Arts

Gold and silver vessels were made, usually past casting, for use by the elite and these very often evidence signs of Persian influence in their shape and the motifs used to decorate them. The designs were likely carried by Persians in person, fleeing the Islamic invasion and settling in China. Potters then applied these ideas to their ain medium (equally did painters) and they included leaf patterns, grapevines, floral chains, and the squat pilgrim bottle. Fifty-fifty human figures on such vessels - especially musicians, merchants and soldiers - are directly taken from Persian tradition. Textile patterns were another inspiration for Tang potters and other popular motifs included lotuses and flowers.

Glazed Tang Dynasty Camel

Tang potters were now more technically proficient than any of their predecessors. New color glazes were developed in the period and include blues, greens, yellows and browns which were produced from cobalt, iron and copper. Colours were mixed, too, producing the three-coloured wares the Tang period has become famous for. Rich inlays of gold and silver were also sometimes used to decorate Tang ceramics.

In the northern areas of China at that place was a tradition for placing figurines in tombs and these were fabricated of ceramic. Common forms are man figures, horses and camels, with parts made from moulds and so assembled, all with brightly painted details which are in marked contrast to the predominantly monochrome paintings of the period. Another source of colour was glassware - most often made in yellow-browns and bright blues. Other minor arts created decorative objects in carved precious and semi-precious stones, lacquer, inlaid woods, amber, and woven, died, printed and embroidered silk.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1130/the-art-of-the-tang-dynasty/

0 Response to "How Did the Emperors During the Tang to Qing Dynasties Influence Chinese Art History"

Post a Comment